1001 Leaders: EuclidKids LLC begins as a friend helps a friend’s 5 year old

Marcia Cooke is the author of two beautiful toys, called Powers of Two and Binomial Squares. They can be used to explore infinity, series, multiplication and proportions, place value, and equations with young children. Marcia likes to meet children and parents to play math together. From the vantage point of a high school teacher, Marcia shares her wisdom about playful, deep, beautiful mathematics with young children.

Marcia Cooke is the author of two beautiful toys, called Powers of Two and Binomial Squares. They can be used to explore infinity, series, multiplication and proportions, place value, and equations with young children. Marcia likes to meet children and parents to play math together. From the vantage point of a high school teacher, Marcia shares her wisdom about playful, deep, beautiful mathematics with young children.

In our 1001 Circles series, we feature math circles stories from the point of view of a circle leader, who acts as an invisible tour guide. In 1001 Leaders, the companion series to our 1001 Circles, we put the spotlight on the leaders themselves. What got them started and what keeps them going? What are their math dreams and worries? If you lead a math circle, an engineering club, or an informal playgroup, we would like to hear your story or interview you. Write moby@moebiusnoodles.com to talk about your adventures.

How did you get into design for young children?

My teaching career is unusual. I am a high school teacher, but I started as an elementary school teacher with an extensive background in using manipulatives. I took higher-level university math courses, but it was my own learning to use manipulatives, and observing children, that made a big difference. All of a sudden I found math learning so much easier, and intuitive. I think that’s because in my own mind, math understanding was not restricted to symbols, but expanded to dimensions and images. It made it easier for me to understand high-level mathematics. Gradually, I went into high school teaching, and became the chair of the math department.

Our history teacher asked about good mathematics for her 5 year old. Together, we invented the puzzles. Then her husband said we should form a company, EuclidKids LLC, because the puzzles had so much effect on their daughter’s learning. The puzzles are very similar to Key Curriculum pieces in the 1980s. I used to play those games with my 1st graders, and a disproportionate amount went to be very, very good students. This knowledge has been around, but people are not using it enough. Maybe because it’s more suited to homeschool or Montessori than a traditional classroom.

Can you give an example of what you understood through manipulatives?

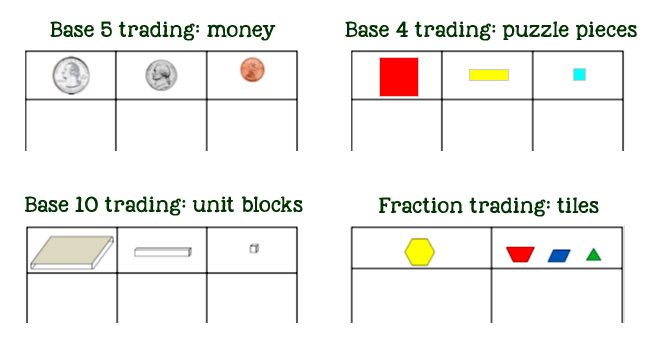

There are so many instances when my own study of mathematics has been improved by learning to use math manipulatives, and they are so varied that I am having trouble making a brief response. Trading games and grouping activities help 5-7 year olds understand place value. Place value concepts are based on exponents and geometry – the connection I saw through manipulatives.

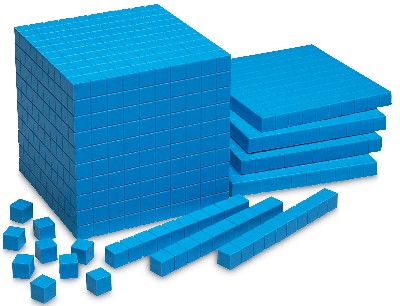

If we think of x as a length, then x2 is a square region, x units wide by x units in length. Similarly, x3 is a cube, x units long, x units wide, and x units deep. Even learning to use base-ten blocks to understand place value and regrouping adds a spatial reasoning element that deepens mathematical understanding.

What are the trading games you mentioned?

One to three children sit in front of an adult “banker.” The children have a place value mat in front of them. This mat is divided into 2 to 4 place value columns. The column farthest to the right is the ones column. When a player rolls the die or spins a spinner to determine how much, the banker pays her in ones. When she has the base number of ones, the player trades for the next unit. The base number can be adjusted to the developmental level of the child. For example, a pre-kindergarten student might play in base-five using a mat with column headings depicting pennies, nickels, and quarters. Six and seven year olds can play base-ten games. Children can also play with fraction pieces and wholes. The winner is the first child to obtain the agreed-upon number of the objects in the leftmost columns, such as two quarters or five hexagons.

What is it all about for you? What will change in the world when more people use these approaches?

In educating young children, we tend to think of teaching them numbers and counting. We teach them numbers in terms of quantity. Of course, quantity is important, as well as associating quantity with symbol. Math is equally a study of dimension. When you introduce young children to the area model, they focus on the length of the sides (1D), and the area of the region that is filled in (2D). From the first, second, and third dimensions, exponents come in. This way children operate on objects with their hands! You help young children to create visual imagery that later will suddenly make sense in algebra courses, and become associated with expressions like x2.

Children who engage in spatial reasoning tasks do better in advanced math courses. The goal of calculus courses is to help students associate symbolic reasoning with images. For example, an equation with its graph. Manipulatives help students integrate counting and measuring, as in many historic uses of mathematics. Even long ago, people weren’t just counting: they also had to measure distances and land. This bridge is ancient. Something that starts as pretty and interesting to young children is helping to create the visual imagery they need later on.

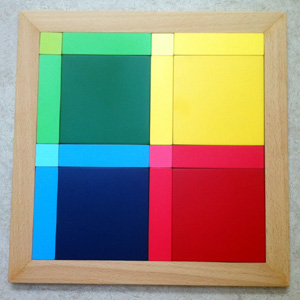

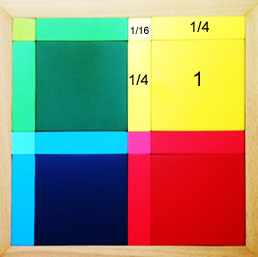

There is an element of beauty that mathematicians talk about. When we play with binomial squares with young children, we are just talking at first: here is dark red, light red… What colors are pretty together? That grows into associating intensity of the color with the size of the piece. The color varies, and the size is another variable. A Montessori education is all about helping young kids develop their powers of observation – even at the beginning, when children see the puzzle not mathematically, but as a piece of art, and enjoy rearranging it.

Picture: two-variable (covariation) games from the Moebius Noodles book

What will be different for young children who have had these experiences? They will find mathematical learning more intuitive. They will ask their own questions, such as, “How many squares can you make from the puzzle pieces?” Instead of place value being explained to them verbally, it will come naturally, or the verbal explanation will make perfect sense. There will be less anxiety about math learning.

Perimeter and area are too often taught by rote, but they can be taught intuitively. Children can see and feel perimeter as the edge of the square, and area as the two-dimensional space within. Kids have difficulty – many, many kids do – because we focus on counting. That is, we focus on number as a count instead of number as a length. For example, the document for the Common Core geometry standards has an image that is similar to the binomial square puzzle. This image is used for teaching fourth graders to multiply 1 1/4 by 1 1/4. Students often think the answer is 1 1/16, but it is not. It’s a four-part multiplication, which is intuitive with the area model. 1*1, 1*1/4, 1/4*1, and 1/4*1/4 are the four products you need to add up. The puzzle can be used to teach why.

What are the benefits of advanced ideas like dimensions, or different bases in the trading game?

I believe adults should not use the Binomial Squares and Powers of Two puzzles to impose higher levels of teaching upon young children. It would take the joy out! These are universal ideas that any person can understand: dimension and space. Allow children to enjoy the puzzle, interact with the puzzle, and put it together in many different ways… Later, you may ask some questions, similar to the questions kids ask: “How many squares can you make?” You can play a base 4 trading game. For example, if the small square is 4, then the big square is 16, because it fits that many small squares (four by four). This helps to introduce place value just by playing the little game. These manipulatives integrate counting, measurement, and dimensions. Hopefully, the child will associate the learning with pleasant, exciting time of exploration later in life.

How do you know when the time is right to start asking questions?

When a child responds to the question with interest and engagement, that’s the right time. If the child ignores the question, it means she is not ready to engage in that way. One of the wonderful things about trading games is that I have never known a child between the ages of 5 and 7 who doesn’t love them, and as the grown-ups share that joy, they are also learning how to ask questions.

If a 5 year old is enjoying putting puzzle together, it is not a good time for questions. If the child is focused on the colors, she may not respond to questions about other topics, such as “Can you put together squares made of different pieces?” Ask questions about what the child is paying attention to.

Here are sample questions from our materials that accompany the Binomial Squares puzzle.

- Explore combinations

- How many ways can the puzzle be put together with the little squares at the center?

- How many ways can the puzzle be put together with the big squares at the center?

- Problem solving

- Can you make a square using four pieces?

- Can you make a square using nine pieces?

- Proportional reasoning

- How many small squares make up a rectangle?

- How many rectangles make up large square?

Ask more open-ended questions. Jerome Bruner had a wonderful research project with children ages 5 to 7. He divided the subjects into two groups. The task was to fetch a piece of chalk from a transparent box without leaving your seat. He gave the children short rods, connecting clamps, and hooks. In one group, he taught children how to retrieve the chalk. In the other, he gave the kids the materials and let them play without explaining or demonstrating. Only after they played did he ask them to get the chalk. In the first group, children gave up if they did not succeed immediately. But in the second group, children were more inventive: they made multiple attempts, with different strategies.

In his book The Process of Education Bruner argued that even young children could engage with challenging material. In his constructivist model children approached such material through three stages: handling materials, forming visual images, and using symbols – in his terms, enactively, iconically, and symbolically. Bruner, who taught for many years at the Harvard School of Education, advocated “a science of toys.” Such toys give opportunities for physical manipulation that leads young minds to form images.

I know other researchers say manipulatives are not magic: that they don’t do any good if adults don’t structure learning in some way. That’s why in Montessori schools teachers ask questions. I say even playing with the visual imagery alone will be a benefit.

Research says that one of the perceptual differences between adults and young children is that children tend to pick out one feature of the puzzle, such as color, and focus on it. In other words, they have trouble integrating different qualities of the object. That’s why I am opposed to things like teddy bear counters. Yes, they are adorable, kids enjoy them, but they can also distract children from the idea of counting, because they may be thinking about teddy bears. Children older than 7 are much more capable of interacting with physical objects in multiple ways.

Will children focus on different qualities of objects on different days?

I would say yes, definitely, but I don’t know if it is days, weeks, or months. It could be a long time for young kids. I have seen kids interact very intensely with the puzzle over several days, and be very interested, then not interested for months. They come back in six months or a year later, ready for questions like, “How many small squares equal the rectangle?” The puzzle’s use as a learning tool is spread over several years.

Posted in A Math Circle Journey, Make

Math mind hacks: Solve it many ways

Math Mind Hacks is a series of mini-posters about quick, smart activities that grow mathematical minds. Today’s poster is inspired by a quote from George Polya, a mathematics educator most famous for his work on accessible, meaningful, fun problem-solving techniques. The quote came to me via Alexandre Borovik of the De Morgan Forum.

Posted in Grow

1001 Leaders – Interview with Jane Kats

This is an interview with Jane Kats, an early childhood educator, math circle leader, author and math enthusiast.

Jane talks about her math circles, what parents can do to help kids enjoy math, and what they should avoid. Jane shares a couple of activities for you to try with your children.

In our 1001 Circles series, we feature math circles stories from the point of view of a circle leader, who acts as an invisible tour guide. But math circle leaders have to do more than tell stories. They bring together the kids and the math, so that the end result, the circle, is more than the sum of its parts. In 1001 Leaders, the companion series to our 1001 Circles, we put the spotlight on the leaders themselves. What got them started and what keeps them going? What are their math dreams and worries? If you lead a math circle, an engineering club, or an informal playgroup, we would like to hear your story or interview you. Write moby@moebiusnoodles.com to talk about your adventures.

When it comes to early childhood education, Jane seems to do it all, from organizing math circles and family game nights to leading summer camps in Russia, Germany, France, Israel, and the US. In between, she also updates her blog (in Russian). Her energy and love for math are both inspiring and contagious. Her blog and her books, some of which are available in English, are overflowing with games, ideas and insights into how children learn – and not just math.

We asked Jane about her math journey and the advice she can share for helping young kids discover the beautiful adventurous math.

Let’s begin!

Moebius Noodles: Tell us a bit about yourself, please.

Jane Kats: I am 40 years old and have two teenagers; Galina is 14 and Grigoriy is 16. I like to play games, draw, talk to people, travel, and share things that I love, such as games and math. In high school I was in an intensive math program and loved to participate in various math olympiads.

When my children started school, I began leading a math circle for kids in elementary grades. Over time, I began a circle for younger kids (preschoolers and kindergarteners).

I enjoy coming up with ways to explain math problems to children and I am patient if they don’t know or don’t understand something.

MN: What are some of your worries and dreams about your work? How does it feel, doing what you do?

JK: I believe that the biggest mistake adults make is the attitude that “you don’t need to understand, only to memorize the answer”. It doesn’t work! Children who memorize the multiplication tables don’t always understand when to use them.

It is sad that for so many children and adults, math is disconnected from life and is associated only with arithmetic. Topics such as symmetry, graph theory, projections, logics are not being considered. Math teaches one to think, so it should not be reduced to arithmetic!

MN: You do a lot for family math: camps, playgroups, parent consults, materials… How did you start? What keeps you going?

JK: Actually, it’s not just math, but also board games, crafts, and play acting… But math is my love. It saddens me to see that many people associate math with boredom and rote memorization. I’d like to give children the joy of coming up with their own solutions, discoveries and experiments.

MN: Imagine someone who is just starting on a similar path, or maybe yourself when you first started. What would you recommend to that newbie?

JK: You can try things, you can create your own problems, you can change game rules on the fly. The important part is to believe that children love to find out new things; they love to learn! Children can learn not in order to get stickers or stars, but just because it is interesting to them.

MN: You said that math is your love. Unfortunately, many parents do not share your feeling.

JK: Yes, I know that many adults grew up with the idea that they do not know or love math. And oftentimes they communicate this idea to their children. I try to show parents and teachers that math is very beautiful, show my favorite math games and activities, and show that one can simply play with math. And I repeat over and over that it is not scary or shameful to not know something or to not be able to do something. We all don’t know or can’t do something, but we can learn. We can break a problem into many parts and solve each part.

MN: Many parents want better math experiences for their children, but do not have the opportunity to join an existing math circle. What can they do, particularly if they suffer math anxiety or fear math?

JK: If parents themselves dislike math or are afraid of it, then the least they can do is to avoid generalized statements such as “math is difficult” and “math is boring” and “I don’t understand this, so I can’t help you here”. In my article, “Math for Dessert”, I have not just games, but also specific examples of things kids might not understand and what they might need help with.

Many adults have favorite and not so favorite topics in different disciplines. It is ok. Parents may look for other adults and kids who love math and get to know them better. Or look for math camps.

MN: What can parents who firmly associate math with arithmetic do? Do you know of any math circles that are led not by mathematicians or math teachers or engineers or programmers, but by adults who didn’t understand math back in school, even disliked it?

JK: Well, I am not a mathematician. Even though I graduated from high school in a math program, I have a degree in linguistics. My kids solve many of the complex math problems better than I do. That’s why I like working with little kids – I am ready to understand that math is complex and ready to help them through their challenges.

MN: When you work with kids, particularly with very young kids, how do you know that they understand what you are telling them?

JK: I am very cautious about various tests and quizzes. I share Alexander Zvonkin’s [mathematician, math educator and an author] idea that timely questions are much more important than dictated answers and that sometimes it is better to spend a year solving a problem on one’s own than to listen to someone else’s detailed explanation.

Sometimes I give kids difficult problems, above their level, to see how they deal with these. This is not a test, but rather a diagnostic tool for the teacher, something to think about.

In general it is a complex topic, how we check child’s understanding. It requires many specific examples. It mostly depends on the ages of the kids, the level of readiness, and on the talent of the teacher.

If I have a group of preschoolers, then I usually know their skills. I might ask one of the kids to name numbers that are neighbors of the number 3, and then help and show manipulatives. I might ask another child from the same group to name neighbors of the number 19 or ask which number has 37 and 39 as its neighbors. The kids who cannot answer these questions yet, they learn by listening to the answers.

With the first-graders, if we do an activity in which we must split a shape into two congruent shapes, then I start with something very simple so everyone in the group can get the right answer. Later on, when working on more challenging problem, if kids cannot figure it out, I might offer them a simpler version with the elements of the original problem to nudge them in the right direction.

MN: Earlier you mentioned that emphasizing memorizing over understanding is the biggest mistake. Some parents say that memorizing first will make it easier for a child to understand why and how it works.

JK: Yes, this is a mistake made by many teachers, and many parents. I believe it is a very serious mistake. In my view, it is a fundamentally flawed approach. A child does not memorize the meaning, just the words, like a rhyme, and doesn’t understand how to use it.

We have a game called “1, 2, 3, Look!” where I use a box with several compartments. When the kids aren’t looking, I put small groups of 2 to 4 similar objects, like buttons or chestnuts, into the box. Then I show the box to one of the kids for a brief moment and the child must guess how many objects were in the box. When they see 3+1+3 objects, some kids quickly respond with 7, while others cannot answer until I show the box again long enough for them to count the objects. The fact that they memorized the words “three plus four is seven” does not help them.

MN: Some parents agree that understanding is better than rote memorization, but are worried that while working on understanding their child will fall behind academic requirements. Others believe that understanding alone is not enough and a child must have a certain level of fluency that can be reached only through rote memorization. Your opinion?

JK: Understanding is more important than rote memorization. Fluency is useful and convenient, and is reached not by rote, but by playing various games. Card games do more for fluency than flash cards.

MN: Many parents do not trust in their own abilities to help their kids learn. They are afraid of making irreversible errors, damaging the kids somehow. Your advice?

JK: I think every parent can find a subject or an area that brings them and their kids joy when explored together. For some it’s math. For others it’s spending time outdoors. For others yet, it’s singing or dance or board games or gardening. I believe it is more important to first find this common interest and then to show kids how you deal with complications that arise.

If parents don’t know much about math, they can frequently be of even greater help to their kids because they will think and talk through the problem slowly, without skipping steps.

MN: What if a child says that he hates math? What then?

JK: I would offer logic games such as Set or Ghost Blitz; math crafts, such as kusudama, symmetry games, or building with toothpicks; puzzles, such as the ones offered by Thinkfun. Then I would tell the child that this too is math. I think many children don’t know how many beautiful and interesting areas there are in math. For me, math circle is a way to show kids the richness of math problems, to teach them to think and reason instead of simply applying a suitable algorithm. It gives kids the chance to experience the joy of finding a solution.

MN: Would you share with our readers a favorite math activity or two?

JK: Stop-Go is one of our favorite games with younger kids. When I say “Stop-1”, the player must stand on 1 leg. “Stop-4” means 2 legs and 2 arms. There are several solutions for “Stop-3”.

We also like playing The Monsters Game. We roll a die and if it shows 5, we draw a monster with 5 heads. Next, we roll the die one more time and draw that many arms. Another roll and we draw that many legs.

MN: You have a very intense schedule – math circles, game nights, camps all around the world. And you write books! How do you stay energized, enthusiastic, and passionate? How do you deal with the burn-out?

JK: Yes, I have a full schedule, but I get help from volunteers. I enjoy coming up with ideas together, doing things together, and sharing ideas. If I get tired, I go camping or hiking. It helps me recharge.

If you have questions for Jane or would like to learn more about her circles, camps, and books, let us know!

Posted in A Math Circle Journey, Make

1001 Circles: an environmental geologist wants to save the world, runs a Math Club

Debbie Vane is an environmental geologist turned mentor in mathematics and science. She has developed a math club for homeschool students ages 6-14, including her son, to help them learn problem-solving strategies. In the club, everyone works on the same concept, but solves different problems. Debbie supports mixed-age groups, because they are more representative of the real world.

Debbie Vane is an environmental geologist turned mentor in mathematics and science. She has developed a math club for homeschool students ages 6-14, including her son, to help them learn problem-solving strategies. In the club, everyone works on the same concept, but solves different problems. Debbie supports mixed-age groups, because they are more representative of the real world.

Here is Debbie Vane’s interview for 1001 Circles, a series of stories that show what a math circle might be like, from the point of view of circle leaders. We hope these stories will inform and inspire you to lead a circle of your own. If you lead a math circle, an engineering club, or an informal playgroup, we would like to hear your story or interview you. Write moby@moebiusnoodles.com to talk about your adventures.

Please tell us about yourself. What are your dreams regarding students and mathematics?

From an early age, I wanted to save the world, really. After spending years as an environmental geologist cleaning up soil and groundwater, I became discouraged by the lack of commitment of big business to clean up their act. I decided the best way to facilitate change was to educate future generations. As a teacher, I instill a love of learning and stewardship of the planet by showing that everything is connected. My background as a scientist naturally led me to teach math — the language of science. Today, as a homeschooler of my son and other children, my goal is to inspire a love of learning of math, break down negative patterns from past experiences with math, and empower students to be the creators of their knowledge. I am less of a teacher and more of a mentor, assisting each student to find their innate talents and set their own learning goals.

What helped you to start the club when you decided it’s needed? What kept you going?

I had taught middle school math for a few years. The greatest impact on learning was always cooperative projects. I decided to start a Math Club for homeschoolers, using projects and simulations as the spine of the club. The enthusiasm and excitement of the kids in the club confirmed that the club was needed and enjoyed by all.

How does it feel to have a wide range of ages together? How do you adapt activities?

Prior to homeschooling, I had never experienced or taught in a multi-age class setting. Having a class with kids ranging in age from 6 to 14, I quickly saw the benefits! For example, I offered a problem-solving unit using an Interact program called MathQuest. Kids traversed MathLand in teams. They earned travel dots by solving and writing word problems. Along the way, the kids drew fate cards, which were always entertaining, and purchased supplies to help them navigate the path.

In one group, there was a 9 year old and a 13 year old. The two students approached problem solving differently. One student was visual and the other student needed to express their thought processes out loud. The 13 year old would draw a picture of the problem, and the 9 year old would verbalize her understanding of the drawing. They worked together until they had a shared understanding and solved the problem.

A benefit of multi-age classes is that the students rarely compare themselves to others. They recognize everyone is of a different age, so there is no sense of competition to be better than one another. There is a general acceptance that everyone is unique, with different levels of skills. There is more cooperation in the class. A 13 year old recalls their skills and challenges when they were 9 year old. They are patient, helpful, and feel like they are a mentor to the younger student. Sometimes, the younger child may have a better understanding and the roles are reversed. I model that all of us have strengths and weaknesses in math and that comparing ourselves to others isn’t useful for developing our understanding. My ultimate goal is for kids to feel comfortable with their skill level wherever they are, and to believe that their worth isn’t tied to what they know but to who they are. This is the reverse of the current competitive world.

When we were learning the problem-solving strategies, each child received different word problems to solve that were appropriate for their age and skill level. Parents always asked me if it was way too much work to create problems for each individual student. My response was always that education needs to be tailored to individual needs. While it was “extra” work for me, it was worth it because I saw growth in each individual, not only in skill level but also in confidence.

Can you share an activity from your club?

I like Marcy Cook’s tile activities. They require critical thinking, are challenging, and don’t ask kids to write to solve problems. The students like the activities. Who doesn’t like to solve a puzzle? The tile packet activities range from operations with numbers to geometry concepts and algebraic reasoning. Students work on a tile activity by themselves, and then ask another student to check their work and offer different solutions. Here is my photo of a tile activity card.

What would you recommend to someone who is thinking of leading a math club or math circle for the first time?

I would recommend to start small and stay within your wheel house. Choose content that you have mastered so that you have confidence to mentor the students in all areas of the topic.

I also believe that it is so important to let the students direct the learning. Go with their interests. Find a way to bring the content into their arena, and you will have willing and eager students.

Finally, embrace and celebrate mistakes. The author Neil Gaiman said, “Make interesting mistakes, make amazing mistakes, make glorious mistakes.” If a student makes a mistake a lot of times, they equate that to not being smart or capable. We need to help students see mistakes as opportunities to learn. I intentionally make mistakes and let them correct me! I laugh when I make a mistake, and model that it doesn’t affect my confidence, my self esteem, or my desire to persevere and solve problems.

Posted in A Math Circle Journey, Grow