Math Storytelling: The Day my First Grader Fell in Love with Numbers

Stephen Taylor first wrote about Zometool adventures for our 1001 Circles series. Now Stephen shares a more personal story, to celebrate Math Storytelling Day on September 25.

For some, the love of mathematics grows gradually, over time. Other people experience love at the first sight of a math game or a tricky puzzle. Many grown-ups who love math, if you only ask them for their math story, can trace the feeling to an initial obsession with a single activity! Read Stephen’s tale to see how parents can notice, support, and nurture these feelings…

I have two young kids, now 6 and 8 years old. My wife and I have put much effort in teaching our kids from a very young age. We threw out the TV, and have played numerous games with our children. Like Maria Droujkova, we believe that what you learn as a young child you learn incredibly well, in a very natural manner, and that it will serve you through life. We also believe that teaching with love, kindness, and lots of involvement is not a chore, but fun for the parents as well as the kids.

As we get older we cannot but absorb the built-in assumptions of the society. We now watch our kids enter school, and see both the value of our efforts, and also how the opportunity for them to learn freely is quickly taken away by the school system. My particular goals have been to teach my kids the concepts and vocabulary of knowledge, easy and fluid methods for learning, and a love of learning and problem-solving. Imagine my dismay when midway through the first grade, I noticed my 6 year old Kai did not really love arithmetic and numbers! The games we had played had been mostly conceptual, with a lot of pattern recognition, such as Chess, Traffic Jam, Chinese Checkers, Mastermind, Pentago, Blockus 3D, Lego, and Zometool. So I got to thinking about number games, and remembered how as a kid loved to play roulette.

I bought an inexpensive used roulette set. When my kids became sufficiently curious as to what was in the package, I opened it up and started playing with my family, the neighbor, and his two kids. I do not believe in teaching formal rules before the start of a game. I just let the kids learn the rules along the way – kind of the way they learn a language. I soon found that the kids absolutely loved the thrill of the spinning ball, the sorting, grouping and counting of their chips, and the simulation of the casino environment. Yes, I hammed it up a bit: calling “no more bets” as the spinning ball started to slow down, and offering free drinks to players who had just suffered a loss – this one caused shrieks of delight! In turn, I was delighted to see the children’s fascination with the pace of the game, winning and losing according to the spin of the wheel, their choices of bets, and their effortless understanding of the numbers. I must add that along the way I did coach them on the evils of gambling and casinos. My kids now know you are highly unlikely to win big in a casino, and if the casino sees you winning too much, you are summarily thrown out – how unfair!

The game of roulette has three concurrent number systems running at all times. First, there are the numbers 1-36, 0, and 00 on the wheel itself. They are selected at random by the spinning ball that drops into one of the 38 wheel slots. Second, there are the corresponding 38 numbers on the mat, and their many categories: black and red, odd and even, rows, thirds and halves of the board, and finally the zero and double zero. The last two tilt the game odds in favor of the house. Third, there are the players’ and casino’s chip counts, going up and down with random winning and losing.

I was not able to teach the kids the finer details of the probability of winning and losing, but they certainly got the gist of it by trying different bets and observing the outcomes. For example, a good exercise is to blot out the zero and double zero and then have kids place equal bets on red and black, odd and even, or each of the 36 numbers. They soon see that under such a system the total chip counts of the players and of the house remain constant. Under that system, at each turn players’ gains (that is, house’s losses) from the winning number equal total players’ losses (that is, house’s gains) from all the losing numbers. However, when you uncover zero and double zero, the house start to win.

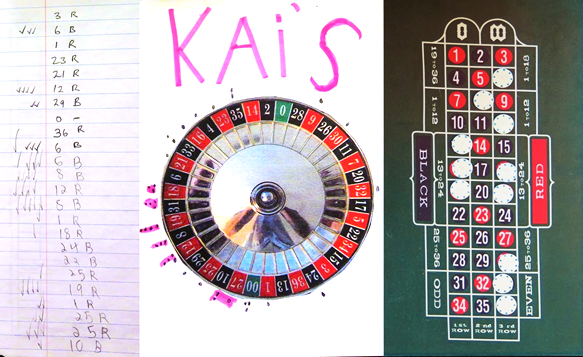

After playing the game for a couple of weeks, I said to Kai: “Let’s see if the wheel is off balance, and if we can figure out how to beat the casino”, which, in his mind, meant beating his friends, sister, and mom. One Sunday morning, while everybody was out, we started to spin and spin the wheel and record the results. My son had just learned how to tally, so he was the scribe. He quickly realized what we were trying to do, and it produced great motivation, especially after he saw that certain numbers come up more frequently. After all, it was just a toy wheel and not very well balanced. At his insistence, we spun the wheel nonstop for two hours, while he kept track of how frequently numbers came up. What better number practice can you get? Kai developed his own little system for counting the frequency of numbers. It wasn’t the most efficient system, but it was original, and it worked. We also plotted the numbers in a simple visual way, which he totally understood – and how could he not? You can see his workings in the figures below.

Professionally and personally, I am very interested in probability and risk applied to games, investing, and designing large facilities. In such situations, one has to understand the risks of events such as floods and earthquakes, and the costs and benefits of reducing these risks. I feel that sharing my knowledge and interests with my children (and my friends’ children) is a core parental responsibility. To see kids grab that knowledge, even tacitly through a game, is thrilling. It adds value to my years of study and, yes, it strokes my ego. What’s more, almost every time I play a game some kid comes up with a startlingly fresh and unusual approach and I end up learning too.

As the pattern emerged clearer and clearer, Kai realized that we were onto something very valuable. Thus our important findings were to be kept secret, so that he could beat his mom and 4 year old sister when they came home. He memorized the 8 or so best numbers and then hid the recording book. I wasn’t sure yet if we had a strong enough winning formula. Later it turned out that we had a good advantage over the house, which became huge when compounded turn by turn. I also knew I was favoring my son like a deus ex machina, but he had to see his effort rewarded. For all his research effort, he got to play the central stage in a performance that could surprise, delight, and enlighten others.

When my wife and daughter returned, out came the roulette set. Because of the potential for gambler’s ruin (a random string of bad luck), I dealt out 50 chips, rather than the usual 30 chips we had previously dealt, and off we went. Lo and behold, the wheel was off balance enough for Kai’s system to work. With a sufficient buffer of the initial 50 chips and a good edge in probabilities, compounding turn by turn, Kai was soon in the money, betting heavier and heavier following his intuition, and winning more and more chips. (See William Poundstone’s book Fortune’s Formula for optimizing bet size according to your edge.) Eventually, Kai broke the bank and held all the chips. My wife, still in the dark, was astounded: she had no idea that the boy had “rigged” the game!

All the while Kai had been zealously sorting, counting and grouping chips of various denominations, watching the spinning numbers, correlating these to his bets on the board, thinking of better strategies, thinking of how much to bet, watching the casino’s money, and lending money to his mom and sister as the casino broke them. His mind was full of numbers. Spin by spin I could almost see new synaptic connections being made in his brain. His strategy was improving. This went on for two hours, and this after two hours earlier in the day spinning and recording! My wife, daughter, and I were also having fun. Yes, everyone was having hours of fun with numbers, and my first grader had spent 4 hours in one day doing just arithmetic – without any coercion!

The game went on so long that eventually we had to send the kids to bed. This involved packing up and taking away Kai’s huge winnings. This did not go down well, and he was in tears. I did not realize how strongly attached he was to his chips, and I was perturbed at this attachment. Was I teaching my kids to become obsessed with money? Kai’s tears soon dried up as he just had to tell his mom and his sister how he had won at roulette. Kai brought out his recording book and everything was explained, which was another proud moment – and a math exercise.

Of course after this game of roulette we had to play the game again and again. Our neighborhood friends and their mothers, uncles and aunts, and everyone was invited to play. The family had been sworn to secrecy. Kai was a hero and people said that they wanted to take him to Vegas on their next visit. I always countered this by whispering in his ear that the casinos use well balanced wheels, and if they did see him winning big, they would take him into the dark back alley and rough him up. He seemed to get the message as he would repeat it. (See the fascinating History Channel documentary Breaking Vegas – The Roulette Assault, where an out of luck family develops a system to determine the off balance of casino wheels to win big and how they are roughed up and eventually broken by the casinos.)

How did people enjoy Kai’s “show”? His sister picked up on the excitement, and wanted to spin the wheel and record the bias too! I usually explained to the neighbor parents what Kai and I had done fairly early, so they knew it was about experiments and learning, rather than cheating. They were accepting of “those things nerdy engineers without TVs do with their kids.” Usually Kai would show the other kids “the trick” quite soon after demonstrating he could win. They often struggled to understand, not having spent hours spinning and tallying. When the kids understood, they immediately wanted to use the trick to beat their parents! None of the kids were upset with Kai. On the contrary, they showed appreciation for sharing his trick.

After a while, I bought another toy roulette wheel and waited for the next game of roulette, cunningly positioning myself as casino’s banker. As expected, Kai used his system to soon have more chips than anyone else, at which point I announced: “The casino is not stupid”, and pulled out the new wheel. Kai was shocked and was not sure what to do. He continued betting his system on the new wheel, which was highly unlikely to have the same imbalance as the old wheel. Soon the house odds knocked him down and ate up all his earnings. He was not happy with this little game of life that I had inserted. In fact, he was in tears. Yet he soon recovered, and set out to find the bias of the the new wheel.

I experience a lot of emotion and worry in choosing approaches to teaching my kids. I have had to work very hard to understand my children’s personalities and their boundaries between fun learning, and frustration or anger. Although learning does seem to continue even during bouts of frustration and anger. I feel good seeing tremendous progress in my kids’ mental abilities, a strong attachment to me, and a desire to learn. If left to themselves, kids bounce back quickly from frustration and anger, so by feeling blue about it, I am not helping them or myself. I remember my own frustrations as a kid; now I believe it is a part of learning, not necessarily bad. It is interesting to note that some Asian cultures are much more inclined than we are to give their kids difficult problems and let them be frustrated. I mostly, but not always, avoid pushing the hot buttons and crossing the frustration boundary. I also delay difficult discussions to a point at which the discussion can be rational and unemotional.

From this experience my son saw utility in numbers. The amount of arithmetic practice from the gazillion games of roulette and wheel spin tests helped him surge ahead. Since then we have found that other games with numbers, such as card games, dice games, and Monopoly, are a good way to teach our kids arithmetic. I still prefer the concepts and have not stopped teaching those. But arithmetic is important too: it helps the kids do well at school and to feel good about their skills. I don’t think that my kids will be attracted to gambling as they grow older: the novelty will not be there, and they now have the inside knowledge coupled with the stories they have heard from me about the evil casinos. Kai quickly grew to lose his attachment to his winnings. He can now win or lose and move on. Roulette is no longer a favorite game, but it was a great teacher. Kai’s love of numbers has not waned and over time he has become very strong at arithmetic. Mathematics has been his favorite subject at school since the middle of first grade and one memorable day.

Related Posts

Posted in Make

Leave a Reply